Plaintiffs M. Therese Burdo (Ms. Burdo) and Robert T. Miragliuolo (Mr. Miragliuolo) and defendants Terrance Murphy and Valerie Murphy (Murphys) own abutting lots on Proctor Road in Chelmsford. In this action brought under G.L. c. 40A, § 17, the Plaintiffs appeal a variance granted by the Chelmsford Zoning Board of Appeals (Board) to the Murphys to construct a new house on their vacant lot within the side yard setback, which would be fifteen feet closer to the Plaintiffs' property than permitted by the setback. Subsequent to an order denying the Murphys' motion to dismiss, this court remanded the matter to the Board for further findings. The Board issued a decision after remand in which the Board again granted the variance to the Murphys. Thereafter, the Plaintiffs filed a complaint after remand. After trial on the Board's decision after remand, I find that the Plaintiffs have standing to challenge the variance and uphold the Board's decision in granting the variance for the side yard setback. Because, however, I find that the Murphy's two abutting lots have merged, I hold that the Murphys' vacant lot is not buildable and annul the of the Board's decision.

Procedural History

Plaintiffs filed their complaint pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17, on September 19, 2012, appealing a decision of the Board granting a variance to the Murphys. On July 9, 2013, the Murphys filed Defendants Terrance and Valerie Murphy's Motion to Dismiss (Motion to Dismiss), along with the Statement of Facts for Defendants Terrance and Valerie Murphy's Motion to Dismiss, the Appendix of Exhibits for Defendants Terrance and Valerie Murphy's Motion to Dismiss, and the Memorandum in Support of Defendants Terrance and Valerie Murphy's Motion to Dismiss. Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants Terrance and Valerie Murphy's Statement of Facts, their Opposition to Defendants' Motion to Dismiss, and the Affidavits of M. Therese Burdo and Philip Christiansen were filed on August 8, 2013. The Board filed Defendant Chelmsford Zoning Board of Appeals Joinder in Co-Defendants' Motion to Dismiss on August 12, 2013. The Murphys filed the Reply Memorandum of Defendants Terrance and Valerie Murphy in Support of Their Motion to Dismiss on August 21, 2013. The court heard argument on the Motion to Dismiss on August 23, 2013, and took the motion under advisement. On August 19, 2014, the court issued an Order Denying Defendants the Murphys' Motion to Dismiss.

On June 16, 2015, the court ordered the case remanded to the Board. Plaintiffs' Proposed Remand Order was filed on June 23, 2015 and Defendants' Motion for Order of Remand was filed on June 25, 2015. On June 25, 2015, the court issued an Order of Remand. On December 4, 2015, a Complaint After Remand was filed. On March 2, 2016, a pre-trial conference was held. A view was taken on July 7, 2016. Trial was held on July 7-8, 2016. The Plaintiffs' Motion in Limine was denied. Exhibits 1-30 were marked. Testimony was heard from Phillip Christiansen, Curt Young, M. Therese Burdo, Terrance Murphy, and Jeffrey Brem. Plaintiffs' Post Trial Brief was filed on November 14, 2016. Post-Trial Memorandum of the Defendants, Terrance Murphy and Valerie Murphy was filed on November 17, 2016. Closing arguments were heard on December 2, 2016, and this case was taken under advisement. On April 26, 2017, the court issued a Decision and a Judgment. On May 8, 2017, Plaintiffs' filed a Motion for Reconsideration. On May 21, 2017, the Murphys filed an Opposition of the Defendants to the Plaintiffs' Motion for Reconsideration. The court heard the Motion for Reconsideration on May 22, 2017, and took the matter under advisement. In accordance with the court's Order Allowing the Motion for Reconsideration and Vacating the Judgment of even date, this Amended Decision follows.

Findings of Fact

Based on the view, the undisputed facts, the exhibits, the testimony at trial, and my assessment of credibility, I make the following findings of fact.

1. The Plaintiffs, Ms. Burdo and Mr. Miragliuolo, own and reside in a single-family home located at 179 Proctor Road, Chelmsford, Massachusetts (Burdo Property). Exh. 1, ¶ 1; Exh. 14.

2. The Murphys reside at 183 Proctor Road (House Lot). The Murphys also own 181 Proctor Road (Subject Lot), a vacant lot abutting the House Lot. The Murphys have owned both these properties since December 24, 1986, when the two lots were conveyed to them by a single deed from Arthur S. Bentas. Exh. 1, ¶ 3; Exh. 13.

3. The Murphys' properties are described as "Two certain lots of land" in their deed, and the deed refers to a subdivision plan showing them as two lots, Lot A and Lot B. At the time of the purchase, both lots were undeveloped. Since then, the Murphys have built a residence on Lot B, the House Lot. Part of the reason the Murphys initially delayed development of Lot A, the Subject Lot, was that they were waiting for a sewer connection to be installed. Each of the Murphys' lots has a separate water and sewer connection, and the Murphys have paid a sewer betterment fee on each of their two lots since those began being assessed. The Murphys' lots have been assessed separately at all times. No structures straddle the two lots, but an extensive wetland area does exist over and along the shared boundary line. There is a stream that comes from offsite onto the House Lot, crosses the front portion of the Subject Lot, and exits through a 30 foot culvert under Proctor Road. Tr. 1:130-133, 148-149; Tr. 2:25-26; Exh. 1, ¶ 4; Exhs. 2, 12-13; View.

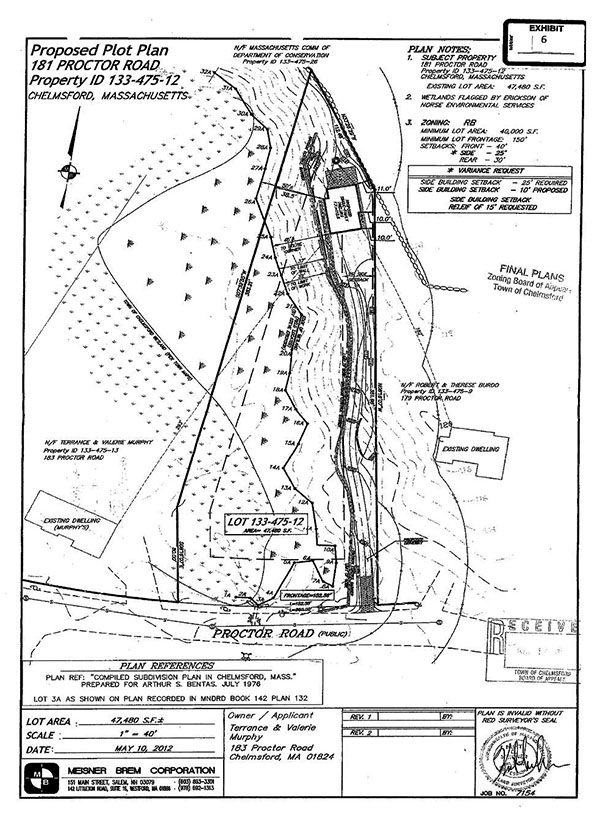

4. The Burdo Property abuts and is adjacent to the Subject Lot on the side opposite from the House Lot, as shown on a plan attached as Exhibit A. Both the Burdo Property and the Subject Lot have frontage on Proctor Road and abut the Great Brook Farm State Park to the rear. The existing grades around the common boundary line slope steeply down from the Burdo Property across the Subject Lot. Exh. 1, ¶ 8; Exhs. 6-7; View.

5. The Subject Lot is a long and narrow triangular parcel, with approximately 150 feet of frontage on Proctor Road and extending 400 feet to the rear. The topography of the Subject Lot is such that the upland portion, along the sideline adjacent to the Burdo Property and in the rear of the lot, is very steep. The flatter land on the Subject Lot, in the center and extending to the boundary line of the House Lot, is primarily wetlands, which renders a large portion of the lot unbuildable. Tr. 1:138-140, 171-172; Exh. 27; View.

6. A Wetlands and Water Resources Map for the Town of Chelmsford depicts portions of the land in Chelmsford that are classified as wetlands under the Wetlands Bylaw. There are wetlands existing throughout Chelmsford. Exh. 18.

7. The Burdo and Murphy Properties are located in the RB (Single Residence) Zoning District, which is described in § 195-2 of the Chelmsford Zoning Bylaw (Bylaw) as a low density single-family residence district. Lots in the RB District must have a minimum size of 40,000 square feet. The Subject Lot is 47,480 square feet. Exh. 1, ¶ 6; Exh. 5.

8. The Murphys propose to build a 28 foot by 38 foot single-family residence towards the rear of the Subject Lot. Exh. 6.

9. The Murphys applied to the Conservation Commission for waivers from the Wetlands Bylaw. The Murphys submitted to the Conservation Commission for approval a Notice of Intent Proposed Site Development Plan dated October 13, 2011, prepared by Jeffery Brem (Brem) of Meisner Brem Corporation (NOI Plan). The NOI Plan placed the location of the residence in compliance with the 25 foot side yard setback required by the Bylaw, but the location of the proposed residence did not meet conservation requirements for a 25 foot no-disturb setback, 30 foot no-pavement setback, or 50 foot no-build setback. According to the NOI Plan, the proposed house was approximately 30 to 36 feet from the edge of the wetland, but within the wetland buffer zone. A six foot high retaining wall is proposed to be placed directly between the proposed house and the wetlands and a proposed erosion control barrier is shown in the same location, but running the length of the property. The Conservation Commission neither approved nor denied the NOI Plan. Instead, during the hearing process, two of the five members expressed a preference for the Murphys to pursue a variance from the side yard setback requirement in the Bylaw so that the proposed residence would be as far away from the wetlands as possible and outside the wetland buffer area. A third member questioned the Murphys' prioritizing zoning compliance over wetlands protection. Exh. 2, ¶ 3; Exhs. 20-22; Tr. 1:150- 151; Tr. 2:6-7.

10. On the Conservation Commission's urging, the Murphys applied for a building permit from the Chelmsford building inspector, Mark Dupell (Dupell). The application included a Proposed Plot Plan prepared by Brem on May 10, 2012 (Plot Plan), which placed the residence farther away from the wetlands, approximately 45 to 50 feet, and just outside the wetland buffer area, but within the 25 foot side yard setback required by the Bylaw. The new location places the proposed house more in the middle of the slope along the shared boundary line with the Burdo Property. Dupell denied the building permit after determining that the proposed house would be located 10 feet from the side property line, which would require a side yard setback variance. Exh. 1, ¶ 5; Exh. 2, ¶ 1; Exhs. 6, 27; Tr. 1:154.

11. The Plot Plan included several features of the overall project for the construction of the house and development of the Subject Lot. A proposed driveway is shown running from Proctor Road to the proposed residence, along the shared boundary line with the Burdo Property. A thick dashed line, testified as being a proposed retaining wall, is also shown in the rear of the Subject Lot along a portion of the common boundary line, parallel to the driveway. An erosion control barrier is depicted in approximately the same location as on the NOI Plan, running the length of the property between the proposed house and the wetlands. Between the retaining wall and the closest corner of the house is a proposed walkway leading to a patio in the rear of the house. The Proposed Plot Plan is attached as Exhibit A. Exh. 6.

12. The NOI Plan submitted with the application to the Conservation Commission was revised by Brem several times, with a final revision date of September 17, 2012 (Revised NOI Plan). The Revised NOI Plan reflects the changes that were made in the Plot Plan. The residence is farther away from the wetlands, approximately 45 to 50 feet, but within the 25 foot side yard setback. The Revised NOI Plan contains more details than the Plot Plan, including landscaping, construction, and the topography of the Subject Lot. It identifies the same retaining wall that is depicted, but not labeled, on the Plot Plan. It shows the height of the proposed wall as six feet and that it will be a block retaining wall. It shows that the walkway is four feet wide. The plan also shows the various types of trees that are on the shared property line. The Revised NOI Plan is still under review by the Conservation Commission pending the outcome of this action. Tr. 1:149-150,160-162; Tr. 2:14; Exh. 7.

13. Based on Dupell's denial of the building permit, the Murphys submitted a variance application to the Board under § 195-9(A) of the Bylaw on May 15, 2012. The application included the Plot Plan prepared by Brem. The variance would allow for a reduction in the side yard setback from the required 25 feet to 10 feet. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 5, 7; Exhs. 5-6; Tr. 1:154- 155.

14. Pursuant to § 195-102(2) of the Bylaw, the Board has the power "to hear and decide appeals or petitions for variances from the terms of this chapter, with respect to particular land or structures, as set forth in M.G.L. c. 40A, § 10." Exh. 5.

15. On May 30, 2012, the Chelmsford Fire Department's Deputy Fire Chief, Michael R. Donoghue (Donoghue), sent a letter to the Board regarding fire safety issues at the Subject Lot based on the Plot Plan submitted to the Board. Donoghue stated that the water supply and the hydrant locations appeared to be adequate, but that he was concerned about access for firefighting apparatus and emergency vehicles. He stated that the proposed driveway lacked sufficient width and entry radius for firefighting apparatus and, as such, he could not approve the plan and asked the Board to make the letter part of their approval process. Exh. 26.

16. During the hearing process, the Board requested that Brem meet with Ms. Burdo to discuss different aspects of the proposed development. After Brem was unsuccessful in meeting or speaking to Ms. Burdo, he sent a letter to her indicating that since the discussion with the Board, he had prepared a landscape screening plan for the Subject Lot which he wanted Ms. Burdo to review and comment on. On August 28, 2012, Brem was able to meet with Ms. Burdo. She commented on the landscape plan and Brem took those comments into consideration in revising the plan. Brem sent a letter to the Board on August 29, 2012, attaching a copy of the revised landscape screening plan. Tr. 1:156-160; Tr. 2:9-10; Exhs. 28-29.

17. The Board held public hearings on June 7, 2012, July 19, 2012, August 2, 2012, and August 16, 2012. The hearings were closed on August 16, 2012, and the Board rendered a decision granting the Murphys a variance from the setback requirement. In a decision dated August 30, 2012, and filed with the Town clerk that day (Decision), the Board found a hardship based on the lot's "unique shape

significant wetlands, and steep grade with [a] ledge." The Decision states that the Murphys are required to receive approval from the Conservation Commission prior to obtaining a building permit and present the Proposed Landscape Screening Plan to Ms. Burdo before August 30, 2012, the date when the Board would file the decision with the Town clerk, which Brem did on August 29, 2012. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 9-11; Exhs. 3, 29; Tr. 2:9-10.

18. As a result of the variance, the proposed home will be 15 feet closer to the Burdo Property and 182 feet from the residence on the Burdo Property. The proposed home will be set back 300 feet from Proctor Road. There is a proposed driveway on the Subject Lot to access the home that will be 50 feet from the residence on the Burdo Property. The elevation of the residence on the Burdo Property is 120 feet while the Murphys' proposed home has an elevation of 112.5 feet. The Murphys' proposed home will also be lower than the elevation of 116 to 118 feet in the backyard of the Burdo Property. The Murphys' proposed home will be located down gradient from the Burdo Property. Exh. 6.

19. On June 25, 2015, the court issued a remand order so that the Board could make further detailed findings on all the elements required for a variance pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 10, address whether a rear yard setback variance was needed, and address the applicability of a contiguous upland requirement in the Bylaw. Exh. 1, ¶ 12.

20. Section 195-108 of the Bylaw defines "Yard, Rear" as "[a] yard extending the full width of the lot and situated between the rear line of the lot and the nearest part of the main building projected to the side line of the lot." "Yard, Side" is defined as "[a] yard situated between the nearest point of the building and the side line of the lot and extending from the front to the rear yard." The Bylaw states that "any lot line not a rear line or front line shall be deemed a side line." Exh. 5.

21. Section 195-108 of the Bylaw defines "Lot Area" as "[t]he horizontal area of the lot, exclusive of any area in a street or recorded way open to public use. At least 80% of the lot area required for zoning compliance shall be contiguous land other than that under any water body, bog, swamp, wet meadow, marsh, or other wetland, as defined in M.G.L. c. 131, § 40." The current definition of "Lot Area" requiring contiguous upland was adopted in 1998. Before then, the Bylaw had no requirements for contiguous upland. The Subject Lot does not contain the requisite 32,000 square feet of contiguous upland. There is approximately 28,402 square feet of contiguous upland area spanning the rear portion of the Subject Lot and crossing onto the rear of the House Lot. Exh. 2, ¶¶ 2, 4, 5; Exh. 5; Tr. 2:25-26.

22. Following the remand order, the Board held a public hearing at which Ms. Burdo again voiced her concerns. Exh. 1, ¶ 13.

23. On November 19, 2015, the Board issued and filed with the Town clerk's office a Decision on Remand, once again unanimously granting the variance to the Murphys and approving the development of the Subject Lot as shown on the Plot Plan (Remand Decision). Exh. 1, ¶¶ 14-16; Exh. 4.

24. The Remand Decision first states that the Board did not find the presence of a rear lot line as defined by § 195-108 that would require a rear setback variance. The Board determined that "due to the very odd shape of the lot, it had four side lines, and not a rear lot line." The Board did find, as an amendment to its 2012 Decision granting the variance, that the proposed residence "met the four criteria of approval, and does not substantially derogate from the neighborhood or intent of the bylaw." The Board stated "[s]pecifically, the very odd configuration of the lot makes improvement of the property extraordinarily difficult due to its unique shape. Also, the presence of wetlands on the parcel makes improvement of the property extraordinarily difficult. Viewed as a condition of the soil, the unique shape and presence and location of wetlands, leaves little upland area to build on." The Board also stated that "the steep grades and ledge are unique topographical features, which by themselves or alone, make this property difficult." They found that these factors "individually or together create a hardship" to the Murphys justifying relief in the form of a variance. Exh. 4.

25. Further, the Remand Decision addressed the issue of merger and the application of the contiguous upland requirement in the Bylaw. The Remand Decision stated:

[T]here is no compelling evidence for the Board to apply an upland requirement to merge the two lots and that considering the lots as merged is not appropriate. Specifically, the Board considered whether the adjacent lots were conveyed by one deed or multiple deeds, whether the lots have been assessed separately or together, the location of structures and whether structures cross lines, whether the owner prepared a plan of the merged lots or otherwise showed an intent to merge them, whether the properties have been physically walled off or otherwise separated from each other. The Board finds that none of these factors compel a finding of merger. No structures cross lot lines. The lots were conveyed as separate lots. The lots have been assessed separately. The lots are separated by a natural, physical barrier, wetlands, which prevents the lots from being used as a single lot. Accordingly, the Board saw no compelling reason to apply the upland requirement or apply it to treat the lots as merged.

Exh. 4.

26. Plaintiffs appeal the Remand Decision of the Board. They claim that the proper requirements for issuing a variance were not met, "there is nothing unique about" the shape, topography, or soil conditions on the Subject Lot, and the Murphys do not suffer a hardship. Plaintiffs allege that as a result of the variance they will suffer from increased density, reduction in privacy, loss of view, decrease in property value, safety infringements, and instability to their property.

27. At trial, Ms. Burdo testified that she and her husband, Mr. Miragliuolo, purchased their property because of its isolated location, its view of the Great Brook Farm State Park, and in reliance on her realtor's statement that the Subject Lot was unbuildable. Ms. Burdo stated that her rear and side yard are currently very private. She and her family use these areas for gardening, recreation, and entertaining. They have a back deck as well, which they use for grilling and eating meals. Ms. Burdo also enjoys sitting on the deck when she drinks her coffee and reads the newspaper in the morning. Ms. Burdo stated that the height and close proximity of the proposed house and driveway on the Subject Lot to her residence and yard area would cause a loss of privacy and diminish her view of the state park. She stated that she would not be as concerned about loss of privacy if the house was built according to the setback requirement because the Subject Lot slopes down away from her property, putting the house at a lower elevation, farther away, and less in her line of sight. Ms. Burdo noted that the view of the Subject Lot was more obscured during the summer when the vegetation is out, and more visible during the winter months. View; Tr. 1:70-73, 77-83, 99, 106-111.

28. Ms. Burdo was also concerned that the installation of the retaining wall would affect the water filtration and cause trees and shrubs that sit near or on the border of the shared property line to die. Ms. Burdo was worried that the dead trees would be more susceptible to fire or wind knocking them over, causing harm to her property. She stated that the length of the driveway and insufficient turning radius would inhibit the fire department's ability to adequately respond in the event of a fire. She said her opinion regarding fire safety was based on testimony given by Curtis Young, the letter from Deputy Fire Chief Donoghue, and her own common sense. She did not consult with a fire expert. Tr. 1:108-111, 122-123, 126-127.

29. In addition, Ms. Burdo attested to the potential impact on her property's value due to the close proximity of the proposed house and driveway. She stated that all of the properties along Proctor Road in the neighborhood back up to the state park and have houses relatively in the middle of their lots. In contrast, the proposed house on the Subject Lot would be built in the rear of the lot, and not centered and close to the side line. She stated that the location of the proposed house would reduce the open air and open space on her property, which every other house in the neighborhood still enjoys. Ms. Burdo believed that this did not fit with the character of the neighborhood and its nonconformity in proximity to her property would diminish its market value. There were no formal appraisals done on the Burdo Property or any evaluation to indicate what impact the proposed house would have on the value of the property. Ms. Burdo

stated that she did consult the Chelmsford tax assessor records for the assessed value of her property, not including improvements, and found that the value in 2015 was $185,000 and it had increased by approximately $15,000 in 2016. Because I found in my Order Denying Defendants' Motion to Dismiss that lost property values was not an interest protected by the Bylaw and, thus, not a valid basis for standing, a conclusion I reiterated in denying Plaintiffs' Motion in Limine, I do not consider this testimony. Tr. 1: 95-97, 99.

30. Phillip Christiansen (Christiansen), a registered professional civil engineer, testified regarding the proposed retaining wall to be built along the shared boundary line with the Burdo Property. Christiansen reviewed the Revised NOI Plan and determined that the face of the retaining wall would be within two feet of the common property line, about six feet high, and would begin about halfway down the driveway to almost the end of the patio in the rear of the house. The top of the retaining wall would be at elevation 118 feet and the bottom of the retaining wall would be at elevation 112 feet. The retaining wall would be located approximately eight feet from the corner of the proposed house at its closest point. Christiansen stated that given the location of the house, the four foot wide walkway, and required landscaping, there is little to no room to move the retaining wall away from the common boundary line. He testified that in order to construct the retaining wall, the soil must be excavated below the finished grade at the foot of the wall. That excavation cannot safely be accomplished by excavating a vertical cut. Rather, the excavation must be sloped for safety reasons. The Revised NOI Plan states that the wall will be a block retaining wall. Christiansen stated that a typical block retaining wall of this size requires either large blocks approximately three feet in width, or the use of mesh fabric embedded in the soil behind the wall to anchor it. Christiansen opined that because of the depth of necessary excavation, the necessity of sloping the excavation, and the width of the improvements associated with the wall, the retaining wall could not be constructed without excavating 15 to 20 feet back from the face of the wall. He stated that if the Plaintiffs do not give their permission for that excavation it would not be possible to build a block retaining wall in that location because it would require trespassing onto the Burdo Property. I credit Christiansen's testimony. Tr. 1:30-33, 35-36, 38-43; Tr. 2:19; Exhs. 6-7.

31. Curtis Young (Young), a wetlands scientist with degrees in forestry, also testified about the proposed retaining wall on the Subject Lot. Young testified that the location of the retaining wall was very close to the shared property boundary and that there are several existing trees and saplings that are physically on the property boundary which could be impacted. Based on his review of the site and the location of the trees, Young concurred with Christiansen's determination that 15 feet would need to be excavated to build the retaining wall. In order to construct the house, driveway, and walkways proposed, Young testified that the Subject Lot would need to be re-graded to create a level area within the slope. He concluded that eight to ten mature trees would need to be removed, while others would be adversely affected due to cuts that would have to be made into their root systems. Cutting into the roots affects the structural stability of the trees and exposes the additional risk of mortality through wind damage. He estimated that there would be a 20-40% impact on the root systems of trees and shrubs located near the retaining wall. I credit this testimony. Tr. 1:51, 53-64, 66; Exhs. 6-7.

32. Young also stated that the retaining wall could cause hydrology issues from the water draining at a higher rate than the trees and shrubs in the area can absorb. Young testified, based on his site visit and soil information provided from the National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), that the soil around the location of the proposed wall was a sand and loam complex called the Charlton and Hollis complex. This type of soil is made up of more fine material than just sand. It is a strong upland soil, and it is characteristic of a wetland soil. Young stated that the Charlton complex has enough fine material that water goes through it more slowly. With the addition of the stones on the retaining wall, Young opined that this would cause the water to move through the soil more quickly and, in turn, prevent the trees and vegetation in the area of the retaining wall from obtaining the proper quantity of water to survive. Young attested that the dead trees would present an increased fire hazard that could cause damage to the Burdo Property in the event of a fire. Tr. 2:27-39; Exhs. 6-7.

33. Jeffrey Brem (Brem), a registered professional civil engineer with soil evaluator approval, testified as to several aspects of the proposed development of the Subject Lot. In 2011, Brem began working on the plans for the proposed house for the Murphys. Over the course of his work Brem developed the NOI Plan and the Revised NOI Plan submitted to the Conservation Commission, and the Plot Plan submitted to the Board. Brem acknowledged that the NOI Plan originally filed with the Conservation Commission showed a design of the proposed house that complied with the 25 foot setback requirement. Tr. 1:134-136, 150-151; Tr. 2:7; Exhs. 6, 7, 22.

34. Brem disagreed with Christiansen's testimony regarding the amount of excavation required for the retaining wall because Christiansen was testifying in regards to the Revised NOI Plan, which is not the plan approved by the Board and has not been approved by the Conservation Commission. Since it has not been approved, Brem noted that the plan was subject to revision and thus, improper for Christiansen to rely on it in his analysis. The Plot Plan that was approved by the Board shows very little detail concerning the retaining wall. The Plot Plan doesn't label the dashed line as a retaining wall, nor does it show the proposed height or what type of wall that would be constructed. Brem stated that the retaining wall could be built without trespassing onto the Burdo Property and without requiring as much excavation. Brem gave no testimony as to what the proper excavation amount would be nor what excavation would be required if the wall were moved to another location. I do not credit Brem's testimony that the retaining wall can be relocated and installed without trespassing onto the Burdo Property. Tr. 1:160-163; Tr. 2:7, 14-15; Exhs. 6, 7.

35. Brem also disagreed with the testimony given by Young that the retaining wall would have an impact on the hydrology. Brem stated that because the retaining wall would be at a lower elevation than the trees, rainwater falling on the Burdo Property would be able to get to the trees before reaching the wall. He testified that the soil in the area was highly permeable sand and gravel known as a sandy esker. Since water moves through the sandy soil at a moderately high rate, Brem opined that the installation of stones in the retaining wall would not change the rate at which the water permeated. Unlike Young, Brem did not rely on soil data provided by the NRCS. He doesn't state how he reached this conclusion, only that he knew it was that soil type based on site constraint mapping he did. Tr. 1:166-167; Exh. 27.

36. Brem testified that the location of the fire hydrant across the street from the culvert on Proctor Road was approximately 300 to 350 feet from the residence, 400 feet if calculated from the path traveled on the road and down the driveway. He stated that 500 feet is the generally accepted distance between fire hydrants on the road, making the distance from the hydrant to the proposed house on the Subject Lot acceptable. Brem prepared a Neighborhood Area Map to show the shape of various lots and location of wetlands on those lots in the vicinity of the Subject Lot within the RB zoning district. Brem used to reside at 63 Proctor Road and is familiar with the neighborhood. Brem stated that based on the landscaping of the properties and the 182-foot distance between the proposed house and Ms. Burdo's residence, there is sufficient privacy, more so than one would expect for the neighborhood. I credit Brem's testimony with

respect to the approximate location of the fire hydrant and that 182 feet between residences is more than adequate for the neighborhood. Tr. 1:173-174; Tr. 2:13-15; Exhs. 19, 27-30.

Discussion

The two questions of law to be determined are whether the Plaintiffs have standing to bring this challenge to the Remand Decision, and, if they do, whether the Remand Decision properly granted a variance under the standards set forth in G.L. c. 40A, § 10. As it is a threshold jurisdictional prerequisite to maintaining an action under G.L. c. 40A, § 17, Barvenik v. Alderman of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 131 (1992), I turn to standing first.

Standing.

In order to have standing to challenge the issuance of the Remand Decision granting the Murphys' variance, the Plaintiffs must be "person[s] aggrieved" by the Remand Decision. G.L. c. 40A, § 17; Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 117 (2011); Planning Bd. of Marshfield v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Pembroke, 427 Mass. 699 , 702-703 (1998). Persons entitled to notice under G.L. c. 40A, § 11, including abutters to the subject property and abutters to abutters within 300 feet of the subject property, are entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they are aggrieved within the meaning of § 17. G.L. c. 40A, § 11; 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012); Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Choate v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Mashpee, 67 Mass. App. Ct. 376 , 381 (2006). The Burdo Property abuts the Subject Lot, and therefore, Ms. Burdo and Mr. Miragliuolo enjoy the presumption of standing.

In the zoning context, defendants can rebut an abutter's presumption of standing in two ways. First, the defendants can show "that, as a matter of law, the claims of aggrievement raised by an abutter, either in the complaint or during discovery, are not interests that the Zoning Act is intended to protect." 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 702, citing Kenner, 459 Mass. at 120. Second, "where an abutter has alleged harm to an interest protected by the zoning laws, a defendant can rebut the presumption of standing by coming forward with credible affirmative evidence that refutes the presumption." Id. at 703. The defendants "may present affidavits of experts establishing that an abutter's allegations of harm are unfounded or de minimis." Id. at 702, citing Kenner, 459 Mass at 119120, and Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 2324 (2006). "Once the presumption is rebutted, the burden rests with the plaintiff to prove standing, which requires that the plaintiff establishby direct facts and not by speculative personal opinionthat his injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community.'" Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33, quoting Barvenik, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 132. At that stage, the "jurisdictional issue of standing will be decided on the basis of all the evidence, with no benefit to the plaintiff from the presumption of aggrievement." 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 701.

In the August 19, 2014 Order Denying Defendants' Motion to Dismiss, I dismissed the claims of standing based on view, property values, and wildlife as interests not protected by G.L. c. 40A or the Bylaw, and determined that the Plaintiffs will not suffer from increased light or noise. In denying the Plaintiffs' Motion in Limine on the first day of trial, I reiterated that property values would not be a basis for standing.

I also found that the presumption of standing had been sufficiently rebutted by the Murphys on issues of stability, fire safety, and density. These three grounds for standing remained available for Plaintiffs to prove at trial. Since the presumption of standing is rebutted, the Plaintiffs bear the burden to present evidence establishing that they will suffer some direct injury to a private right, private property interest, or private legal interest as a result of the Remand Decision that is special and different from the injury the Remand Decision will cause to the community at large, and that the injured right or interest is one that c. 40A or the Bylaw is intended to protect, either explicitly or implicitly. Id. at 700; Kenner, 459 Mass. at 120; Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 27-28; Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721; Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 440 (2005); Barvenik, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 132-133; see Ginther v. Commissioner of Ins., 427 Mass. 319 , 322 (1998).

Aggrievement is not defined narrowly; however, it does require "a showing of more than minimal or slightly appreciable harm." Kenner, 459 Mass. at 121, 123 (finding the height of the new structure to have a "de minimis impact" on plaintiffs' ocean view). In assessing the injuries allegedly resulting from the Remand Decision, I must look at the harms or impacts of the entire proposed construction, not just those that are the result of the variance. See Aiello v. Planning Bd. of Braintree, No. 15-P-1321, 2017 WL 1396540, at *5 (Mass. App. Ct. Apr. 14, 2017); Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 724. The evidence must be both quantitative and qualitative. Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 441. Quantitative evidence "must provide specific factual support" for each injury the plaintiff claims. Id. Qualitative evidence is held to a reasonable person standard. Id. Each of the remaining grounds on which the Plaintiffs rely for their standing is discussed in turn.

1. Stability

Ms. Burdo and Mr. Miragliuolo claim that construction of the proposed house and driveway will undermine the stability of their property in the area along the property line between the Murphy and Burdo Properties. This is a question of safety, an interest protected in the "Purpose and authority" provisions of § 195-1 of the Bylaw (Bylaw intended "to protect the health and safety of . . . inhabitants"). Moreover, the testimony of Christiansen and Young provided credible evidence that the Burdo Property will necessarily be materially altered in order to construct the proposed retaining wall, because of the amount of re-grading that will have to be done to the Subject Lot.

Christiansen testified that there is a six foot grade change between the common boundary line and the proposed driveway. The Subject Lot must be re-graded to accommodate the construction of the house and driveway and this cannot be done without the retaining wall. The location of the house 10 feet from the boundary line, the four foot walkway, and the various trees along the boundary line, necessarily restricts the location of the retaining wall. Building the retaining wall requires excavation of the soil below the finished grade at the foot of the wall. Since that excavation cannot safely be accomplished by a vertical cut, it must be sloped. Because of the depth of necessary excavation, the necessity of sloping the excavation, and the width of the improvements associated with the wall, the retaining wall could not be constructed without excavating 15 to 20 feet back from the face of the wall. Young testified that several trees along the boundary line would also have to be removed and other trees' root systems damaged in connection with constructing the wall. All of these changes, resulting from the failure to meet the minimum side yard setback, would materially alter the stability of the Burdo Property. However, without permission from the Plaintiffs, Christiansen attested that the wall could not be built since it would require trespassing onto the Burdo Property.

In rebuttal, Brem testified that the retaining wall did not have to be in the location shown on the Revised NOI Plan and he could make changes to the Revised NOI Plan since it has not been approved by the Conservation Commission. Brem stated that there was sufficient room to move the wall if necessary and construction could be done without trespassing onto the Burdo Property, although he did not posit where the wall could be relocated. He noted that the wall was to be designed by others and construction details of that design were not approved by the Board in the Remand Decision. Brem disagreed with Christiansen's determination of the amount of excavation required for the wall in its proposed location, but did not attest to what the proper excavation amount would be nor what excavation would be required if the wall were moved to another location. Based on this, the Murphys did not present evidence that, if believed, would warrant finding that the wall could be relocated and constructed so that no trespass onto the Burdo Property would be necessary. I credit the testimony of Christiansen and Young, who provided sufficient evidence that the retaining wall was a necessary component to the re-grading of the Subject Lot for the proposed house and could only be located in the position shown on the Plot Plan and Revised NOI Plan. I find that damage to the lateral support along the common boundary line as a result of the re-grading is not speculative or de minimis. As such, Ms. Burdo and Mr. Miragliuolo have standing based on their concerns regarding impacts to the stability of their property.

2. Fire Safety

The Plaintiffs also claim that the proposed development on the Subject Lot creates fire safety risks. Fire safety interests are protected by both the Zoning Act and the Bylaw. St. 1975, c. 808 § 2A (zoning objectives include "to secure safety from fire, flood, panic and other dangers"); Bylaw § 195-1 (Bylaw intended "to protect the health and safety of . . . inhabitants"). In support of their standing, Plaintiffs rely on testimony at trial given by Young.

Young testified that the excavation for the retaining wall would require the removal of eight to ten mature trees, as well as smaller saplings, on the Burdo Property and would materially damage the root structure of a number of other trees on the Burdo Property. He stated that the damage to the root structure of the trees would cause many of the trees to die. Cutting into the roots also affects the structural stability of the trees and could be damaged or killed from strong winds. Young opined that the installation of the retaining wall would additionally cause water drainage issues and have an adverse consequence on the amount of water available to the trees adjacent to the common boundary line. Young testified, based on his site visit and soil information provided from the NRCS, that the soil in the area of the proposed retaining wall was sand and loam mixture called a Charlton and Hollis complex. This type of soil is made up of material more fine than just sand. Young stated that the Charlton and Hollis complex has enough fine material that water goes through it more slowly. With the addition of the stones on the retaining wall, Young opined that this would cause the water to move through the soil more quickly and, in turn, prevent the trees and vegetation in the area of the retaining wall from obtaining the proper quantity of water to survive. Young attested that all of these impacts expose the trees to a heightened risk of mortality.

Brem disagreed with Young that retaining wall would have an impact on the hydrology, which would increase the mortality of the trees. Brem stated that the soil in the area was highly permeable sand and gravel known as a sandy esker. Since water moves through the sandy soil at a moderately high rate, Brem opined that the installation of stones in the retaining wall would not change the rate at which the water permeated. Unlike Young, Brem did not rely on soil data provided by the NRCS and did not state how he reached his determination of the soil type, only that he used site constraint mapping. I credit Young's testimony, based on his background in forestry and his methodology of using the NRCS data to reach his conclusion, that the retaining wall will alter the hydrology of the soil.

Because the proposed house would only be 10 feet from the trees on the Burdo Property, Ms. Burdo testified that she was concerned that the damaged or dead trees would increase the risk of fire damage to her property. Young opined that dead or fallen trees along the shared property line would be more susceptible to catching fire if there was a fire on the Subject Lot. Although Young is not a fire expert and did not perform any specific evaluations on what the increased potential for the fire hazard could be, I credit the testimony of Young regarding the damage to the trees as a result of the excavation for the wall and that the dead trees would present an increased fire hazard.

Ms. Burdo also stated that the long, narrow driveway proposed on the Subject Lot would not provide sufficient access to the proposed house if there was a fire and should an emergency arise, emergency vehicles would have inadequate access to and would be unable to turn around in the driveway. The proposed driveway is approximately 300 feet long and about 9 feet wide, running straight back from Proctor Road. Ms. Burdo gave her opinion partly in reliance on the letter sent by Deputy Fire Chief Donoghue, which stated that he was concerned about access for firefighting apparatus and emergency vehicles. In the letter, Donoghue wrote that the proposed driveway lacked sufficient width and entry radius for firefighting apparatus and, as such, he could not approve the variance. Donoghue did not testify at trial and Ms. Burdo stated that she did not consult a fire expert herself. Ms. Burdo's concern does not support a finding that emergency vehicles would have inadequate access to the house.

I find credible evidence in the form of testimony by Ms. Burdo and Young that the development of the Subject Lot will increase the risk of harm from fire, as a result of injury to trees. The Murphys provided no evidence to counter the testimony regarding the susceptibility of the dead trees to fire or to mitigate Ms. Burdo's concern over harm to her property from a fire, which is 10 feet from the proposed house, as opposed to harm to her residence, which is considerably farther. The Plaintiffs' claims regarding fire safety are substantial enough to confer standing.

3. Density/Loss of Privacy

The Plaintiffs also claim that they will suffer from overcrowding, as the proposed house will affect their privacy and create more mass in their side yard area. As discussed, the Murphys' variance is from the side yard setback requirements of the Bylaw. It is recognized that setback requirements are intended to protect a zoning bylaw's interest in regulating or reducing density. See O'Connell v. Vainisi, 82 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 691-692 (2012); Dwyer v. Gallo, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 295-297 (2008); Bylaw § 195-1 (provides fire safety and open space regulations); and § 195-2 (2) (defines the RB zone of the Subject Lot and the Burdo Property as a "low-density single-family residence district"). Plaintiffs are not entitled to standing simply because the proposed house will be built within the setback; they must prove harm from the encroachment that is "(1) not de minimis and (2) particularized to" them. Marhefka v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Sutton, 21 LCR 1 , 5 (2013).

Plaintiffs argue that the construction of the proposed house, located 10 feet from their property line, will overcrowd their property, result in a loss of open space, loss of privacy, and the loss of use and enjoyment of their backyard. Ms. Burdo testified that she purchased her property because of its relative isolation and the privacy from neighbors it provided. She enjoys gardening, entertaining, and using her backyard and side yard in other various ways. Ms. Burdo stated that the nearness of the house and driveway will interfere with the use of her backyard and garden, thus infringing on her privacy. Ms. Burdo also contends that given its proposed location on the Subject Lot, the height of the proposed home will also infringe upon her privacy and disrupt her views. The Burdo Property has an elevation of 120 feet at the residence and an elevation of 118 to 116 feet in the backyard. The Murphys' proposed home will be built according to the thirty-five foot maximum height provided by the Bylaw and set on a portion of the Subject Lot that has an elevation of 112.5 feet. Ms. Burdo attested that if placed at the planned elevation, the proposed house would impede her currently unobstructed view of the state park in her backyard and infringe on her privacy. She noted that the view to the Subject Lot would be more visible during the winter than the summer, but that many of the trees that currently provide screening would be removed for the construction of the retaining wall. She stated that she would not be as concerned if the house was built farther way, meeting the setback requirement, because the Subject Lot continues to slope downwards, away from the Burdo Property, which would set the proposed house at a lower gradient and reducing the obstruction to her views and privacy concerns.

The Murphys argue that the proposed home is down gradient, thereby not having any impact on the Plaintiffs' view, privacy, or density. Brem, who used to live in the neighborhood on Proctor Road, testified that the distance between the proposed house and the residence on the Burdo Property was ample and more than what you would expect for the neighborhood. The Murphys also assert that existing vegetation in the area of the proposed home would provide additional privacy. Brem designed a landscaping plan and met with Ms. Burdo to get her input and attempt to ameliorate her concerns. Brem made changes to the plan based on her suggestions. However, as noted by Brem, the landscaping plan, submitted along with the application to the Conservation Commission, has not been approved and was not part of the Board's approval.

Based on my view, and the testimony of Ms. Burdo, which I credit, I find that the privacy in the Plaintiffs' use of their backyard and view of the state park would be lessened by the proposed house. The Murphys have not provided sufficient evidence to address these concerns.

Accordingly, the Plaintiffs have met their burden of standing based on density and loss of privacy.

Merits.

Having found that the Plaintiffs have established standing based on stability, fire safety, and density, I now turn to the merits of the Plaintiffs' appeal, namely, whether the Board, in the Remand Decision, properly granted the variance from the setback requirements of the Bylaw to permit the Murphys to construct the proposed house within the setback and properly found that the Subject Lot and the House Lot had not merged. Before addressing the Board's Remand Decision with respect to the setback, I must first determine whether the two lots owned by the Murphys merged for purposes of zoning, resulting in the loss of the Subject Lot's grandfathered status, and, thus, making the contiguous upland requirement applicable for the lot to be buildable.

1. Merger

The merger doctrine provides that undersized adjoining lots that later come into common ownership after the effective date of the bylaw that rendered them nonconforming "merge" for the purposes of achieving dimensional compliance with the current zoning law. Sorenti v. Board of Appeals of Wellesley, 345 Mass. 348 , 353 (1963). Put simply, the doctrine calls for adjoining land in common ownership to be added to the nonconforming lot in order to bring it into conformity or reduce the nonconformity. Preston v. Hull, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 236 , 238 (2001). The statutory grandfather provision contained in G.L. c. 40A, § 6, incorporates this doctrine by providing protection to certain lots from increases in lot area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirements. Paragraph four of Section 6 contains what is known as the Single Lot Exception:

Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirements of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply to a lot for single and two-family residential use which at the time of recording or endorsement, whichever occurs sooner was not held in common ownership with any adjoining land, conformed to then existing requirements and had less than the proposed requirement but at least five thousand square feet of area and fifty feet of frontage.

G.L. c. 40A, § 6. This exception protects owners whose lots previously conformed with zoning requirements. Marinelli v. Board of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 , 258 (2003). This exception is not available to lots held in common ownership with an adjoining lot, which may be combined, or merged, to reduce or eliminate the nonconformity. Sorenti, 345 Mass. at 353. Paragraph four of Section 6 provides more limited grandfathering protection for lots held in common ownership.

Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard or depth requirement of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply for a period of five years from its effective date or for five years after January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, whichever is later, to a lot for single and two family residential use, provided the plan for such lot was recorded or endorsed and such lot was held in common ownership with any adjoining land and conformed to the existing zoning requirements as of January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, and had less area, frontage, width, yard or depth requirements than the newly effective zoning requirements but contained at least seven thousand five hundred square feet of area and seventy-five feet of frontage, and provided that said five year period does not commence prior to January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, and provided further that the provisions of this sentence shall not apply to more than three of such adjoining lots held in common ownership.

Essentially, perpetual grandfathering protection for separately owned lots is not available to adjoining lots held in common ownership. Rather, lots held in common ownership are entitled to grandfathering only for five years after the effective date of a zoning change, provided they had a lot size of at least 7,500 square feet and had 75 feet of frontage. Marinelli, 440 Mass. at 258. After the five years have run, the lots are combined or merged to reduce or eliminate the nonconformity. G.L. c. 40A, § 6; Sorenti, 345 Mass. at 353. "The common ownership requirement in G.L. c. 40A, § 6, represents a statutory codification of a principle of long-standing application in the zoning context: a land owner will not be permitted to create a dimensional nonconformity if he could have used his adjoining land to avoid or diminish the nonconformity.'" Savery v. Duane, 22 LCR 284 , 289 (2014), quoting Planning Bd. of Norwell v. Serena, 406 Mass. 1008 , 1008 (1990)

The Subject Lot conformed to the zoning requirements when the 1998 Bylaw was adopted to change the definition of "Lot Area." The 1998 Bylaw's requirement of 80% of the lot area to be contiguous upland rendered the Subject Lot, with less than 28,000 square feet of contiguous upland, nonconforming. [Note 1] However, the Subject Lot does not qualify for perpetual protected status under § 6 due to its common ownership with the House Lot. "For purposes of §6, lots are held in common ownership' if they are listed as owned by the same party on the most recent instrument of record prior to the effective date of the zoning change." Marinelli, 440 Mass. at 258, citing Adamowicz v. Ipswich, 395 Mass. 757 , 763 (1985). By their deed, the Murphys held the Subject Lot in common with the House Lot when the 1998 Bylaw was adopted to include the contiguous upland requirement that rendered the lots nonconforming. Exh. 13. The five year period of protection for lots held in common having lapsed, the merger doctrine applies to the Subject Lot and the House Lot, and the Subject Lot is not entitled to the grandfathering protection of § 6.

Section 6 is not the end of the grandfathering analysis. Courts have long recognized the ability of a municipality to grant protection for owners of nonconforming lots broader than the protections offered in G.L. c. 40A, § 6. "Many cases establish the full prerogative of municipalities to legislate in a manner which gives far great indulgence to the ability to build upon lots no longer dimensionally compliant with current zoning rules. And one of the indulgences a municipality properly may extent is the lifting of section six's requirement that adjoin commonly-owned lots be merged." Dalbec v. Westport Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 16 LCR 672 , 674 (2008); see Carabetta v. Board of Appeals of Truro, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 266 , 269 (2008); Luttinger v. Truro Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 11 LCR 72 , 75 (2003) ("When a municipality elects to give local by-law protection without the merger requirement of Section 6, that extra indulgence has been upheld by the court."). "Section 6 provides only a floor and . . . a municipality is free to grant more liberal treatment to the owner of a nonconforming lot." Mohr v. Stroh, 21 LCR 249 , 250-51 (2013), quoting DeSalvo v. Chatis, No. 149615, 1991 WL 11259380, at *3 (Land Ct. Sept. 11, 1991).

The grandfathering provision in the Chelmsford Bylaw, however, does not offer more liberal protections than § 6. Section 195-9.A of the Bylaw states: "No structure shall be erected or used, premises used or lot changed in size or shape except in conformity with the

requirements of this article, unless exempted by this chapter or by statute (see MGL c. 40A, §6)." Exh. 5. Section 195-10 of the Bylaw is the only section addressing existing nonconforming lots. It states: "No existing nonconforming lot shall be changed in size or shape, except through a public land taking or donation for road widening, drainage or utility improvements or except where otherwise permitted herein, so as to increase the degree of nonconformity that presently exists." Id. at § 195-10. This provision provides even less grandfathering protection than under § 6. The Bylaw is silent about the circumstances under which a nonconforming lot may have grandfathered status, and does not differentiate between lots held separately or in common. This language demonstrates that Chelmsford did not intend to do away with the merger doctrine by providing a generous exception. Rather, the town chose to rely on the provisions of § 6, including its exclusion from protected status after five years of lots held in common ownership.

The Murphys do not dispute that § 195-10 of the Bylaw does not provide a more liberal grandfathering provision. Instead, they argue that paragraph four of G.L. c. 40A, § 6, is inapplicable because it does not specifically call out an increase in the contiguous upland requirement as one of the dimensional changes subject to be grandfathered. The Murphys assert that the contiguous upland requirement is not a dimensional requirement, but a restriction on the land different from an increase in area, frontage, width, yard, or depth. They contend that because the merger doctrine was designed to lessen dimensional nonconformities, it does not apply where the increased requirement involved the composition of the lot area itself. I find this argument lacks merit.

The Murphys rely on Lamb v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Taunton, 76 Mass. App. Ct. 513 (2010) to support their position that a contiguous upland requirement does not govern lot size. In Lamb, the owner of two nonconforming subdivision lots appealed a zoning board's denial of a request for a variance from the contiguous upland requirement. The zoning board had denied the variance on the basis that the contiguous dry land requirement was dimensional and did not relate to "soil conditions, shape, or topography" within the meaning of G.L. c. 40A, § 10. Id. at 518, citing Tsagronis v. Board of Appeals of Wareham, 415 Mass. 329 , 331-332 (1993) (lot's dimensional deficiencies are not the sort of deficiencies for which zoning relief may be afforded pursuant to § 10). In reviewing the contiguous upland requirement, the Appeals Court focused on how it necessitates a determination of what portions of a lot are dry and which are wetlands as defined by the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act (MWPA). Id. Ultimately, the court found that "[w]hether land is a wetland within the meaning of the MWPA requires one to examine, inter alia, the condition of the soil as it pertains to the presence of water. Unlike dimensional requirements such as lot size or frontage, therefore, the dry lot requirement is directly tied to the presence of a particular natural conditions, namely water, below, in, or on the soil. As such, it falls squarely within the ambit of G.L. c. 40A, § 10." Id.

The decision in Lamb rested on a determination of whether the upland requirement was a dimensional requirement under the definition of G.L. c. 40A, § 10, that could not be cured by a variance. In this case, however, the analysis is whether the upland requirement is dimensional for purposes of paragraph four of G.L. 40A, § 6. If so, the merger doctrine, in paragraph four applies. The Board did not grant a variance from the contiguous upland requirement and that is not the subject of this appeal from the Board. The facts of Lamb did not involve the application of the merger doctrine and the Appeals Court did not decide whether such contiguous upland requirements fell within the purview of G.L. 40A, § 6. The decision of the Appeals Court in Chamseddine v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Taunton, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 305 (2007), is more applicable to the present circumstances.

In Chamseddine v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Taunton, the Appeals Court treated an increase in the amount of contiguous upland required as a change to the lot area requirement in applying the grandfather protections of G.L. c. 40A, § 6. Chamseddine, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 305 (2007). The purchaser of a residential subdivision lot appealed a zoning board's determination that the lot was subject to current zoning ordinance dimension requirements, including an increase to the amount of contiguous upland required for buildability. Id. at 305-306. The court found that the upland requirement was a dimensional change, like lot area, and, therefore, applied paragraph four of Section 6. At the time of the zoning change, the lot in Chamseddine had sufficient contiguous upland to satisfy the then-existing bylaw. Id. at 306-307. Therefore, the court held that the increase in the contiguous upland requirement did not apply to the lot because it received grandfather protection pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 6. Id. at 308.

Like the bylaw provision in Chamseddine, the contiguous upland requirement at issue here was a dimensional change, an increase to the lot area requirement in the Bylaw, that is subject to paragraph four of G.L. c. 40A, § 6. "Lot Area" is defined in the Bylaw as "[t]he horizontal area of the lot, exclusive of any area in a street or recorded way open to public use. At least 80% of the lot area required for zoning compliance shall be contiguous land other than that under any water body, bog, swamp, wet meadow, marsh, or other wetland." Exh. 5, § 195-108. The language of the Bylaw establishes that the contiguous upland is part of the lot area, changes to which are subject to analysis under G.L. c. 40A, § 6. The Murphys cannot avail themselves of the protection of paragraph four in G.L. c. 40A, § 6. Section 6 excludes protection for non-conforming lots that are (a) held in common ownership (b) with adjoining land such that (c) the adjoining land would bring the nonconforming lot into conformity or reduce the nonconformity. The Board incorrectly determined on remand, without citing any authority, that the lots did not merge and that upland requirement did not apply to this case. The evidence presented shows that the Subject Lot and House Lot were held in common ownership in 1998, the time the Bylaw was amended to include the contiguous upland requirement, and more than five years have passed since that date.

The Murphys purchased the Subject Lot and adjoining House Lot in 1986, by a single deed from Arthur S. Bentas. The Murphys acknowledge that neither of the lots individually meet the contiguous upland requirement of the Bylaw. Deeming the lots merged would render either lot in greater conformity with the contiguous upland requirement. That the two lots have been assessed separately, have separate sewer connections, and there are no structures straddling the shared boundary line does not mean that the two lots have not merged for zoning purposes. The Murphys cannot claim grandfathering protection under § 6, and the Bylaw does not offer more liberal protections. The two lots have merged.

Because I find that the Subject Lot was merged with the adjoining House Lot and did not have any lawful independent existence as a lot for zoning purposes, it is unnecessary to reach the second, more deferential part of the inquiry, in which the court would assess whether the Board's finding no. 3 in the Remand Decision that stated that "the Board saw no compelling reason to apply the upland requirement or apply it to treat the lots as merged," was "unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary." MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 639 (1970). Even if the Board had considered whether the Murphys were entitled to a variance based on the holding in Lamb that contiguous upland requirements may be the subject of a variance request, see Lamb, 76 Mass. App. Ct. at 518, any such decision would be irrelevant since a variance cannot be issued for a change in a dimensional requirement that renders a lot unbuildable. See Dwyer, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 298; Perez v. Board of Appeals of Norwood, 54 Mass. App. Ct. 139 , 142-143 (2002). The two lots constitute one conforming lot for zoning purposes, and the Subject Lot cannot be split off from the rest of the parcel to form the basis for a new buildable lot.

In short, because the Subject Lot and the House Lot have merged, the Subject Lot was not a separate lot that could be the subject of a variance. Therefore, the Board's Remand Decision issuing the variance was erroneous as a matter of law, and must be annulled.

2. Variance

Though I find that the Remand Decision must be annulled because the Subject Lot has merged with the House Lot, for purposes of completeness, I examine whether the Board properly granted the variance for the side yard setback based on sufficient findings made in accordance with G.L. c. 40A, § 10. No one has a legal right to a variance, and variances are granted sparingly. The 39 Joy St. Condominium Ass'n v. Board of Appeal of Boston, 426 Mass. 485 , 489 (1998); Pendergast v. Board of Appeal of Barnstable, 331 Mass. 555 , 557, 559 (1954). To grant the variance, the Board was obligated to find that:

[O]wing to circumstances relating to the soil conditions, shape, or topography of [the Subject Lot] and especially affecting [the Subject Lot] but not affecting generally the zoning district in which it is located, a literal enforcement of the provisions of the [Bylaw] would involve substantial hardship, financial or otherwise, to [the Murphys], and . . . desirable relief may be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent or purpose of [the Bylaw].

G.L. c. 40A, § 10. The standard is conjunctive; all of these conditions must be met to issue a variance. Planning Bd. of Springfield v. Board of Appeals of Springfield, 355 Mass. 460 , 462 (1969); Perez, 54 Mass. App. Ct. at 142. In this appeal under G.L. c. 40A, § 17, of the grant of the variance, the burden is on the Murphys, the people seeking the variance, and the Board to present evidence proving "that the statutory prerequisites have been met and that the variance is justified." Warren v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Amherst, 383 Mass. 1 , 10 (1981), quoting Dion v. Board of Appeals of Waltham, 344 Mass. 547 , 555-556 (1962); see The 39 Joy St. Condominium Ass'n, 426 Mass. at 488. Thus, the Murphys must prove that, with respect to the side yard variance, the Remand Decision contains specific findings that all prerequisites for the variance were satisfied and that those findings are supported by the evidence.

To begin with, the Board's Remand Decision states that "due to the very odd shape of the lot, it had four side lines, and not a rear lot line," and, therefore, no rear yard setback variance was necessary. I find that the Board reasonably treated the Subject Lot as having no rear lot line, but rather an additional side line in the rear of the parcel based on the shape of the parcel and their rational interpretation of the definition of "Yard, Rear" and "Yard, Side" in § 195-108 of the Bylaw. Exhs. 4, 5. In particular, the Bylaw provides that "any lot line not a rear line or front line shall be deemed a side line." Exh. 5, § 195-108.

In granting the variance for the side yard setback at issue, the Board determined that construction of the proposed residence on the Subject Lot "met the four criteria of approval, and does not substantially derogate from the neighborhood or intent of the bylaw." Exh. 4. While thin, these findings meet the requirements of G.L. c. 40A, § 10. The Board discussed the aspects of soil conditions and topography that made literal enforcement of the setback requirement a hardship, and found that relief could be granted without detriment to the public good and without substantially derogating from the intent of the Bylaw. As discussed below, these findings were rational and supported by the evidence presented de novo at trial.

The Murphys' impediment to building outside the 25 foot setback established in the Bylaw relates to the no-build provisions in the Wetlands Bylaw. This is a "circumstance[] relating to the soil conditions" of the Subject Lot. G.L. c. 40A, S 10. The stated purpose of the Chelmsford Wetlands Bylaw is "to protect the wetlands, water resources, flood prone areas, and adjoining upland areas in the Town of Chelmsford by controlling activities deemed by the Conservation Commission likely to have a significant or cumulative effect on Resource Area values." Exh. 21, c. 187, §1A. Chapter 187 of the Wetlands Bylaw provides that it is intended "to protect the Resource Areas under the Wetlands Protection Act, G.L. c. 131, § 40 (the Act) to a greater degree, to protect additional Resource Areas beyond the Act recognized by Chelmsford as significant, to protect all Resource Areas for their additional values beyond those recognized in the Act, and to impose . . . additional standards and procedures stricter than those of the Act." Exh. 21, c. 187, §1B. The Wetlands Bylaw's definition of "Resource Area" includes both wetlands and buffer zones. As shown on the site constraint mapping done by Brem, the Subject Lot has unique soil conditions because nearly the entirety of the parcel consists of wetlands and wetland buffer areas. The Board noted that the presence of wetlands on the parcel makes development of the Subject Lot difficult. Exh. 4.

The shape of the Subject Lot is long and narrow. The Board found that "the very odd configuration of the lot makes improvement of the property extraordinarily difficult due to its unique shape." Exh. 4. The Subject Lot also has very steep grades, with the proposed location of the house one of the few level areas on the lot. View. The Board found that "the steep grades and ledge are unique topographical features, which by themselves or alone, make this property difficult." Exh. 4. The flatter land on the Property is primarily wetland soils and the wetland buffer area, which renders a large portion of the lot unbuildable. The variance will allow construction of the residence in the least steep area of the upland. The Board stated that, "[v]iewed as a condition of the soil, the unique shape and presence and location of wetlands, leaves little upland area to build on." They found that these factors "individually or together create a hardship" to the Murphys justifying relief in the form of a variance. I find that the Board's findings are sufficiently detailed, meet the requirements of § 10, and are supported by the evidence.

For a variance to be granted, the circumstances related to the soil conditions, shape, or topography of the property must be peculiar to the Subject Lot. See Bicknell Realty v. Board of Appeals of Boston, 330 Mass. 676 , 680 (1953). The Murphys introduced evidence, which I credit, demonstrating that these conditions were unique to their property and do not generally affect the zoning district in which the Subject Lot is located. See Campbell v. Rockport Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 21 LCR 676 , 679 (2013) ("If there are other properties within the same zoning district as the subject property that have similar topography, soil, or shape, the first criterion to obtain a variance is not fulfilled."), citing Kirkwood v. Board of Appeals of Rockport, 17 Mass. App. Ct. 423 , 426 (1984). Brem prepared a Neighborhood Area Map to show the various lots in the vicinity of the Subject Lot within the RB zoning district. While many of the lots on the Neighborhood Area Map are long and narrow like the Murphys' lot, they do not possess the unique convergence of wetlands, topography and shape problems that the Murphys face. The presence of wetlands is apparent on some other parcels in the neighborhood, but the wetlands on those parcels do not occupy large sections of the lot as they do for the Murphys' lot. The wetlands, combined with the steep gradient and ledge, which I saw on the view, distinguishes the Subject Lot from other lots in the district.

The Murphys presented evidence of how literal enforcement of the provisions of the Bylaw would involve substantial hardship, financial or otherwise. See Spaulding v. Board of Appeals of Leicester, 334 Mass. 688 , 692 (1956). I credit this evidence. Substantial hardship is found where under unique circumstances it is not economically feasible or likely that the locus would be developed in the future for a use permitted by the zoning bylaw. See Paulding v. Bruins, 18 Mass. App. Ct. 707 , 711-712 (1984). Courts have found that hardship is shown when, absent a variance, the land cannot be used for any purpose permitted by the by-law, and so will have little if any value. Id. (upholding grant of variance based on finding that lot is unbuildable without variance and it has no other use but that of a residential home site). A lesser showing of hardship is required for dimensional variances than for use variances. See Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 725-726 (hardship requirement satisfied by showing it would be economically impractical and not economically feasible as a result of unique conditions affecting locus); Josephs v. Board of Appeals of Brookline, 362 Mass. 290 , 293 (1972) (alternative schemes to bring development into compliance would involve safety hazards or loss of usable space within proposed building); DiGiovanni v. Board of Appeals of Rockport, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 339 , 347 n. 14 (1984) (upholding denial of variance and stating that "[w]here noncompliance amounts to a matter of inches, we might reach a different conclusion"); 6 Patrick J. Rohan, Zoning and Land Use Controls § 43.02(3) (1983). That a lot of land is "non-buildable" under the terms of a zoning bylaw is a factor which a board of appeals should consider in determining whether a hardship exists. Chater v. Board of Appeals of Milton, 348 Mass. 237 , 244 (1964).

In this instance, a strict application of the Bylaw would preclude development of the Subject Lot. The Subject Lot cannot be improved by the proposed residence without a variance from the side yard setback. The Murphys suffer financial hardship in that they purchased two lots for $170,000.00. Without the variance, the Subject Lot, which cost the Murphys $85,000.00, would effectively be rendered worthless. The two lots have always been assessed and taxed separately, and the Murphys have paid approximately $24,000 in taxes on the Subject Lot and a sewer betterment fee of $6,500.00, for a total of $115,000.00 spent on the Subject Lot. Exh. 13; Tr. 1:132-133. Prohibiting the development of the Subject Lot due to a minor side yard setback violation under such circumstances would cause the Murphys to suffer a substantial hardship.

Furthermore, the Board correctly found that the granting of the variance "does not substantially derogate from the neighborhood or intent of the bylaw." The most appropriate use of the Subject Lot is as a residential home site. This use is clearly consistent with uses in the RB District, which is for single-family residences. Exh. 5. Allowing this project will not change the character of the district or endanger nearby properties. Although the Murphys' home would be 10 feet from the Burdo Property line, the residence on the Burdo Property is located 182 feet from the Murphys' proposed home. As Brem testified and I saw on the view, the distance between the residences is more than adequate for the neighborhood. The Murphys included landscaping in their proposed plans to alleviate concerns that the Plaintiffs have with the proximity of the proposed dwelling to the Burdo Property line. Exhs. 28-29. The proposed house is in harmony with the character of the neighborhood and the Board's reasonable conclusion on this matter should not be disturbed. See MacGibbon, 356 Mass. at 639 (court must give deference to local board's decision and may only overturn a decision if "based on legally untenable ground or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary"); Cavanaugh v. Di Flumera, 9 Mass. App. Ct. 396 , 400 (1980) (unless a use significantly detracts from the zoning plan for a district, the Board's discretionary grant of a variance must be upheld). In short, the part

of the Board's Remand Decision granting the variance for the side yard setback was not arbitrary or capricious, and is supported by the evidence at trial. [Note 2]

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find that while, due to circumstances relating to the shape, topography, or soil conditions of the Subject Lot, the Murphys will suffer substantial hardship, the House Lot and Subject Lot have merged for purposes of zoning, making the Subject Lot unbuildable and the variance erroneous as a matter of law. An Amended Judgment shall enter annulling the Board's Remand Decision.

Judgment accordingly.

M. THERESE BURDO and ROBERT T. MIRAGLIUOLO v. JOHN R. BLAKE, JR., BRIAN REIDY, LEONARD R. RICHARDS, JR., PAUL J. HAVERTY, WALTER CHAGNON, EILEEN M. DUFFY, JOEL J. LUNA, and MARK CAROTA, all in their capacity as members of the CHELMSFORD ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, TERRANCE MURPHY, and VALERIE MURPHY.

M. THERESE BURDO and ROBERT T. MIRAGLIUOLO v. JOHN R. BLAKE, JR., BRIAN REIDY, LEONARD R. RICHARDS, JR., PAUL J. HAVERTY, WALTER CHAGNON, EILEEN M. DUFFY, JOEL J. LUNA, and MARK CAROTA, all in their capacity as members of the CHELMSFORD ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, TERRANCE MURPHY, and VALERIE MURPHY.